A Typology of Socialisms in the 21st Century

What separates democratic socialism, social democracy, and communism from one another? A great deal.

Nick French’s post two weeks ago for Left Notes provoked a few interesting reactions that got both of us thinking more about the meaning of democratic socialism. The main question posed to Nick by a number of comrades had to do with the robustness of his distinction between democratic socialism on the one hand and other kinds of socialist politics on the other.

On X, one challenge was posed by a comrade named Nik against the idea that there is a clear distinction between democratic socialists and social democrats. Nik wrote: “I think my issue with this though is European social democrats started off as Marxist and for the most part claimed their goal was socialism until very recently like the 90s.”

In a similar vein, in the comments trenches of Nick’s article,1 Adam pointed out that the line between democratic socialists and some who call themselves communists today is blurry too:

Here in Austria, the Communist Party has found success running on a platform essentially the same as [Zohran] Mamdani’s. Does that mean they’re democratic socialists? In a certain sense, yes, but they still identify as Communists because that’s the specific socialist political tradition they come from – a political tradition that had radically democratic origins that are now being reclaimed, in spite of the tradition’s Stalinist degeneration.

How to respond? Let’s set aside the messier question of specific labels for a minute and try to make some meaningful conceptual distinctions between different kinds of socialist projects, distinguished in terms of these projects’ end goals and means of getting there.

The Socialization Question

The core distinction in Nick’s piece has to do with a project’s orientation to changing the basic property relations in a society. Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of society’s productive assets (the “means of production”) by a small class of capitalists. This economic system produces many problems that all political projects of the left, from the most radical to the most moderate, try to address in some way.

Some projects want to address these problems by lessening the suffering of those on the losing end of the system while respecting and even defending the basic property relations of capitalism. These projects may lay claim to the socialist label out of some combination of loyalty to the tradition they emerged from and a belief that they are still loyal to a set of values that could be called socialist, even if they think those values can coexist with a capitalist economic system.2

Other projects are not opposed to that kind of amelioration but want to go further. They want to restructure the economy as a whole by moving toward a system that combines public ownership and worker cooperatives, potentially with some much-reduced-in-significance private ownership sector. Nick’s piece does a great job of laying out the details of this point, so I won’t go into it further.

Let’s call this issue the socialization question. To rephrase it: Does a socialist project respect private ownership rights, or is it trying to socialize (take under public or cooperative control) most productive assets?

A good illustration of this difference lies in the changes made to the UK Labour Party’s program in the 1990s. In 1918, the Labour Party adopted as part of its objectives the nationalization of much of private industry. The text of Clause IV called for: “the common ownership of the means of production, distribution and exchange.” In 1995, Tony Blair altered the language of Clause IV. Although his new version explicitly identified the Labour Party as a democratic socialist party, it defined socialism in terms of a set of values — solidarity, respect, tolerance — rather than as a new set of property relations. Where the Labour Party had once been for the socialization of the means of production, after 1995 it no longer saw this as an essential element of its version of democratic socialism.3

Another way to think about the socialization question is in these terms: Is socialism a destination? That is, is it a new economic system designed according to a set of values and to be brought about by taking the means of production into common ownership (the position of those who believe socialization is vital to the socialist project)? Or is socialism more like a moral compass? That is, is it exclusively a set of values, which can be realized within the capitalist system (the position of those who oppose the need to socialize the means of production)?

The Transition Question

Adam’s question gets at a different problem of definition. How does a socialist project aiming to socialize the economy intend to achieve its goals? Let’s call this the transition question.

Historically in capitalist democracies, socialist politics has also been split over this question. Socialists of different stripes have made different wagers about how they might come to hold state power. These different wagers often manifest themselves in different approaches to building organizations as well as different focuses for political work, a point I got into in “The Politics of the Three Lefts” last year. For our purposes here, the most important difference is over strategic objectives.

There are those who wager that the most likely and most desirable path to socialism in capitalist democracies would be by means of a democratic road to socialism. These democratic roaders see the election of a socialist government as a key strategic objective of their socialist project. (It’s necessary to specify that this is a position relevant only to capitalist democracies because there can be no democratic road in authoritarian regimes.)

Then there are those who wager that the most likely (even if not necessarily the most desirable) path would be by means of an insurrectionary road to socialism. Insurrectionary roaders see the installation of a socialist government on the back of a mass uprising that overthrows the existing government as a key strategic objective of their socialist project.

That’s the main difference. I say “a key strategic objective” in both cases because forming a government is just one big step on the long road to socialism in both projects. Following the coming to power of a socialist government, both democratic and insurrectionary roaders want it to make progressively deeper attacks on the private property rights of major corporations and big capitalists. And both projects, at least in theory, want to rebuild the structure of the state to put political power in the hands of working-class people and to minimize the power of the capitalist class.4

The smartest advocates of both roads have also always been clear-eyed that a new government — regardless of how it comes to power — will be fatally weakened without popular power behind it. Popular power means having an active and militant base of millions built around a mass party, powerful unions, neighborhood assemblies, and other social movements. That base needs to be able and willing to act independently, and if necessary challenge, a socialist government if it falters. This is the most important element in achieving any socialist transition.5

Socialist Projects of Types I, II, and III

If we combine the socialization question and the transition question we can specify three different types of socialist projects. (The chart at the top of this article illustrates this typology.)

A Type I socialist project is one that respects the economic structure of a capitalist economy and has no ambitions to socialize it.

A Type II socialist project is one that is committed to socializing the economy and sets as one of its key strategic objections the election of a socialist government.

A Type III socialist project is one that is also committed to socializing the economy but sets as one of its key objectives the installation a socialist government through an insurrection.

One Divides Into Two, Two Become One

Coming back to the question of social democracy, democratic socialism, and communism, let’s put the types to use by means of a ridiculous pairing.

In 1964, Maoists in China were locked in a strenuous debate about dialectics and contradictions. Orthodox followers of dialectical materialism defended the slogan that “one divides into two”: Everything contains contradictions inside itself and eventually splits into pieces. The pieces develop from there. Thirty-two years later, in 1996, the Spice Girls released the love song “2 Become 1” about two people merging themselves into a romantic relationship.

The actual labels we use to describe strategic differences in the socialist movement are messy because over the last 150 years one divided into two and two became one many times over, with very little respect for clean semantic distinctions.

To provide a sketchy history of the evolution of these labels in the twentieth century: Before 1914, both future dyed-in-the-wool reformists like the right wing of the German labor movement and future insurrectionists like the Russian Bolsheviks identified as “social democrats” and even saw themselves as being part of the same political project. One divided into two over the course of World War I, however, and by the early 1920s distinctions between social democrats and communists began to map fairly well on to distinctions between Type II and Type III socialists.

In the postwar period, two became one in one sense as communists in most Western European countries increasingly gravitated toward a democratic road. In fact, it was a communist, Nicos Poulantzas, who coined the term “democratic road to socialism.”6 The seemingly obvious distinction between social democrats as Type II and communists as Type III blurred significantly. Both camps began to look more and more like Type II, and the term “democratic socialism” became increasingly fashionable to describe this kind of politics.

But in another sense one divided into two. Many from the social democratic tradition became Type I socialists and surrendered any hope of challenging the capitalist class’s ownership rights over most of the economy’s productive assets. This transition picked up speed in the 1980s and ’90s — there was after all, as Margaret Thatcher put it, “no alternative” to capitalism.

Now, returning to the reactions to Nick’s post mentioned above: Adam is right to note that the historic traditions that the Communist Party of Austria and the Democratic Socialists of America come out of are very different. But as he also notes, their politics today are basically indistinguishable: they both fit comfortably into Type II. Nik is likewise right to note that many social democrats in postwar Europe believed that they were working toward building a socialist economy, they too were at one point Type II.

That’s all to say that history’s twists and turns have left us today with a complicated vocabulary for talking about socialist strategy.

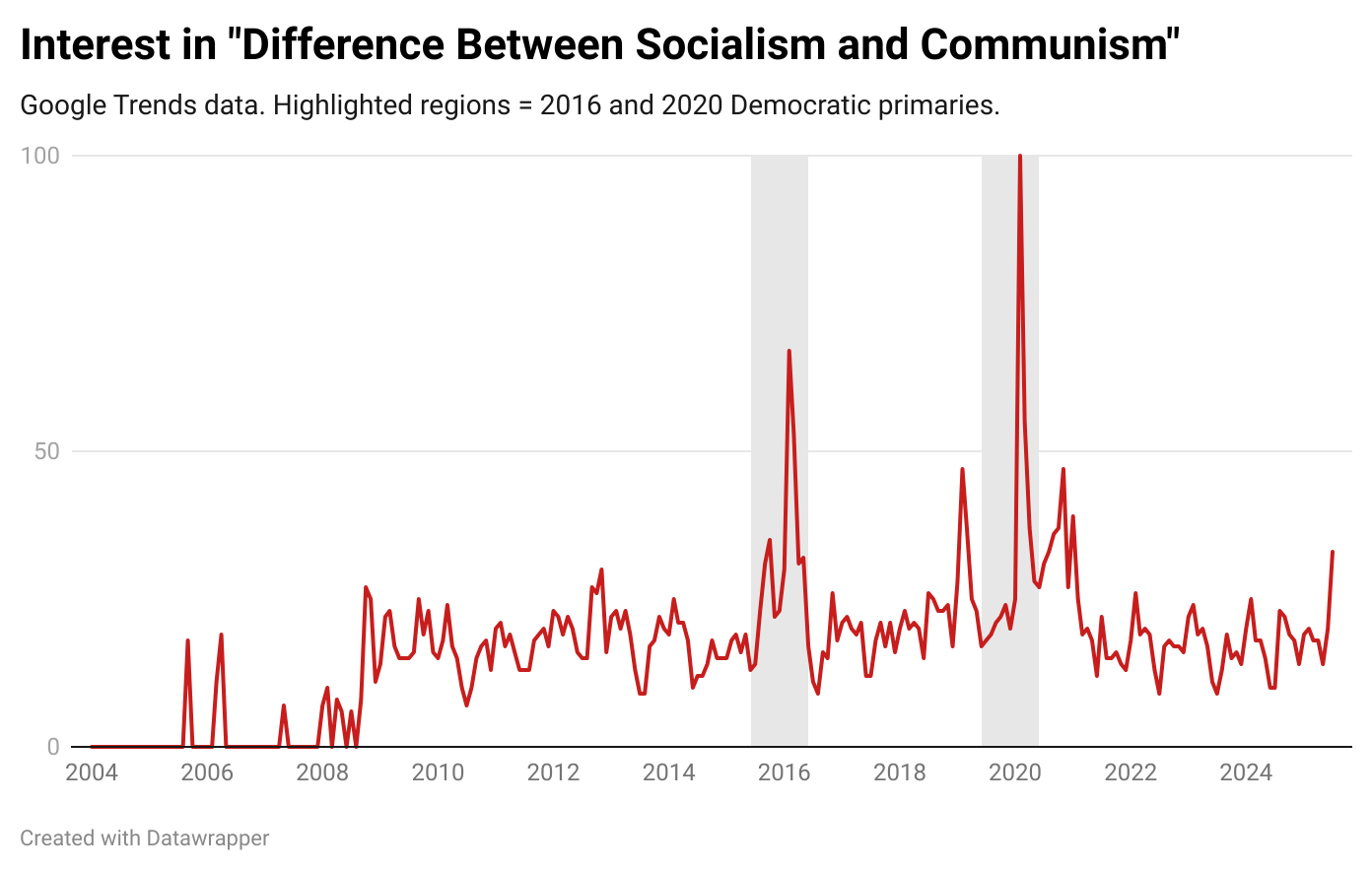

One response to that complexity is to give up on the label game altogether. It’s tempting, but in my mind the fascination with questions like “What is the difference between socialism and communism?” in 2016 and 2020 during Bernie Sanders’s presidential campaigns is a reminder that the popular demand for labels and definitions is high (see the graph below, higher values mean greater interest in the search term at a given point in time). This shouldn’t come as a surprise. Labels help people arrange their mental maps of different sets of ideas and strategies and help them understand political debates.

Debates over how to define the term “democratic socialism” (and communism and social democracy) will continue, and they’re worth engaging in. Socialists will be hard pressed to resist supplying the arguments needed to meet the demand for definitions and distinctions. And since there are meaningful differences between the three types of socialists I’ve described here, there is a value in trying to connect those definitions to these real differences.

It’s certainly true that at the moment the meaning of democratic socialism is contested and the boundaries between democratic socialism and social democracy in particular are not perfectly clean. In the 2020s, both Type I socialists and Type II socialists (I put myself in the latter camp) lay claim to the democratic socialist identity. Discussions over the meaning of that identity are in part a semantic argument. But that semantic argument is also the entry point into a strategic debate about the long-term objectives of the socialist movement. Are we fighting for the kind of social democratic welfare state that many European countries have, and that Europe’s social democratic parties now act (at best) as custodians and conservers of? Or are our sights set higher? As someone who believes that the answers to those questions matter, I therefore also think the debate over the meaning of the labels is worth joining.

A reminder that comments on our posts are open to email subscribers (it’s free!), and we really appreciate feedback.

There’s another interesting question to be asked about the point at which a center-left project aimed at enacting ameliorative reforms ceases to have anything to do with the socialist tradition at all. In other words, what’s the boundary line between socialist and liberal politics? I’ll leave that for another time.

This is also more or less what the new 2025 program of the Swedish Social Democratic Party, for example, says that socialism means: “The goal of democratic socialism is a society of solidarity where all people participate and live free and equal.”

For the sake of concision here, I won’t go into debates about what happens after a socialist government comes to power. Suffice it to say that I think socialists of all stripes often overlook the significant similarities between the challenges awaiting a socialist government that comes to power by a democratic road and the challenges for a government formed by means of an insurrectionary road. In both cases, a new socialist government still faces off against a powerful foe in the capitalist class, and in both cases it will have to work with much of the existing state bureaucracy and figure out how to deal with hostile elements in the police and military. In both cases, a new socialist government will have to make decisions about the pace at which to socialize the economy (a question I’ve written about before). Even the newly formed Soviet Union struggled with this question of pacing in the first ten years of its existence, before Joseph Stalin’s “Great Break” opted for rapid nationalization — with disastrous consequences. And in both cases, a new socialist government will have to decide how to respond to extralegal attempts to undermine or defeat it.

In practice, advocates of both the democratic road and the insurrectionary road have at best been inconsistent supporters of this kind of popular power. Socialist governments have come to power by democratic and insurrectionary means and in many (maybe most) cases that has led to the demobilization and disempowerment of popular movements. That’s a challenge for all socialists to think more seriously about. It’s also a challenge for the “smartest advocates” of both roads that I mention: if the coming to power of socialist governments consistently leads to a decline in popular power, maybe there’s a serious flaw in either the theory of using state power to build socialism or the theory that popular power can sustain a new socialist government once it’s in power — or both.

A good starting point to learn more about this history is the debates over Eurocommunism.

I like the piece but I’d say your note 4 is the most important part, which is not addressed in full. Too many on the left are dreaming about a future and (hopefully) classless society focused on common welfare, but they overlook the fact that an existing ruling/owning/capitalist class must be defeated by some means in order to get there. And that class isn’t going quietly. Nor are they going without first employing massive state violence, which they have at the ready, no matter how peaceful, slow, or democratic the takeover is. They know it’s coming, because they have class consciousness already, and they will fight tooth and claw to keep or increase(!) their power.

We are all guilty at some point of focusing too much on the end goal and not the steps required to achieve it, but some of us are not growing out of that.

Thank you for this clear explanation! It's great to see some "here's where socialisms differ" analysis without the piece reading like some "here's why these people aren't real socialists, unlike my infallible political project!"