Socialists Can't Sit Out National Politics

It’s easy to feel like national politics is a dead end for the left. That’s why avoiding it and focusing instead on local politics and base building is understandable. But doing so is a mistake.

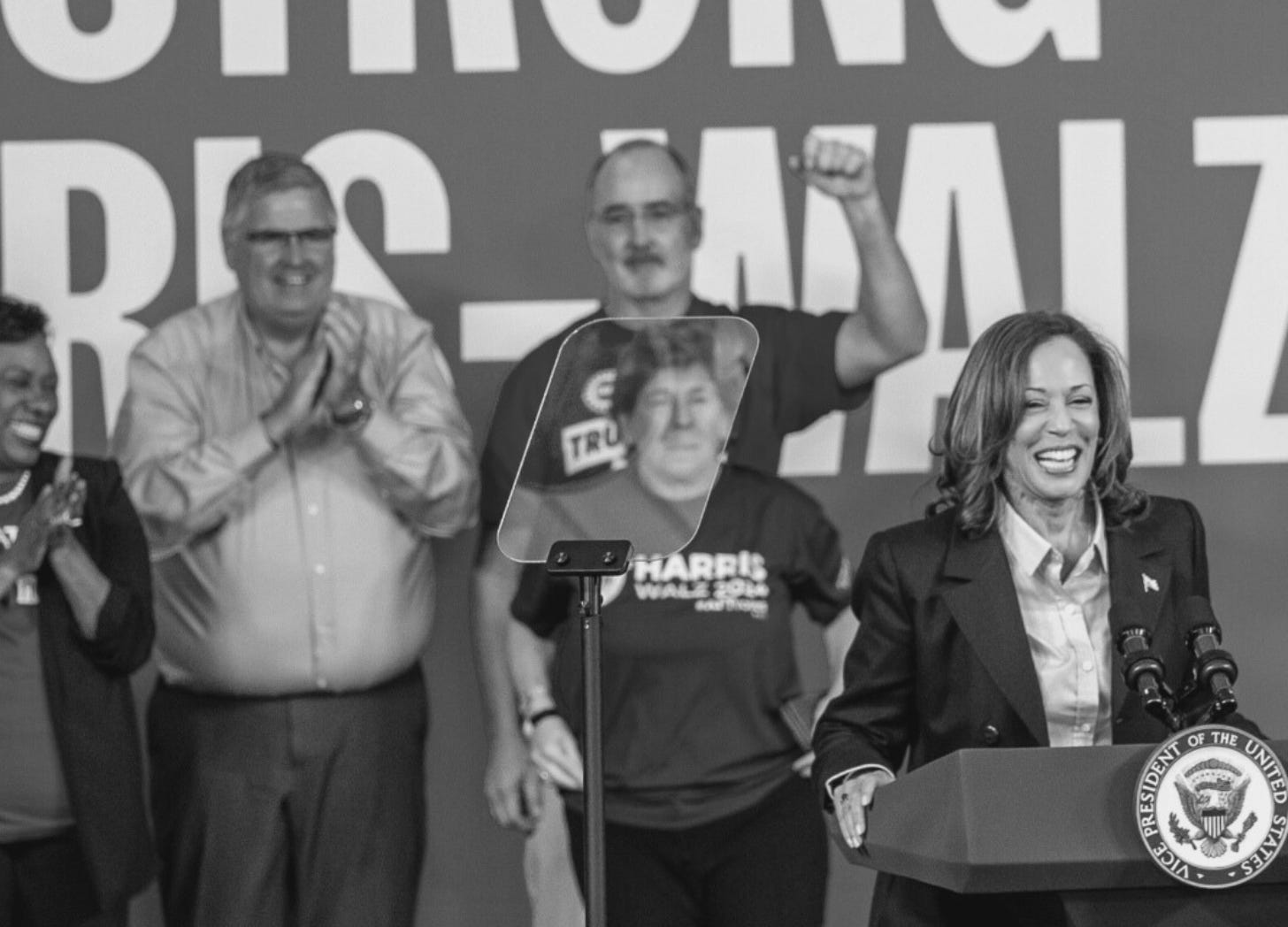

Two weeks ago I published a short piece in Jacobin on what a national strategy for the left under a Harris administration might look like. It focused mostly on what Bernie Sanders and the left wing of the labor movement could do differently in the near future.

The piece took a lot of flack from liberals and those on the left who are defensive of Joe Biden and Kamala Harris. For them, the idea that Democrats would need to be pushed by the left and the labor movement is absurd. The times have rarely been better, they argued, for pro-worker policies and for progressives. Never mind that most people have good reason for not feeling that way, labor union density continues to decline, Donald Trump has at least a 50-50 shot at victory in November, left-leaning projects find themselves on the back foot in many places, and left-wing progressives in Congress are going down in defeat. To me, the situation now should give us pause and force a rethink about what we’ve been doing.

Sharper criticism though came from my left, including from my friend Danny. Danny kindly pushed back on some of the flack I took from the libs. But he wasn’t having the basic premise of my piece either. He summed up his reservations succinctly: “There is a sense in which this is wrong because none of it will happen.”

I think Danny is right to be skeptical that Sanders and organized labor will rise to the occasion, as the recent record is not encouraging. New Democratic administrations never enjoy much of a honeymoon from the corporate world, which sets to work putting pressure on the incoming team from day one. Progressives and the labor movement, however, have generally given new administrations far too much room for maneuver.

It is reasonable to wonder: could it possibly be different this time? That’s what motivated my Jacobin piece. So here I want to offer first a brief restatement of the problem and then second, an answer to Danny’s question. If the pattern seems so set, isn’t it a waste to pin any hope on Sanders and the labor movement changing it?

America’s Downward Spiral

There’s a predictable pattern now to US politics that I am calling the “downward spiral.” We’ve been stuck in it for decades.

The downward spiral goes like this: 1) elect new Democratic administration -> 2) new Democratic administration disappoints base -> 3) “throw the bums out,” elect Republican administration -> 4) Republican administration angers country -> 5) “throw the bums out,” elect new Democratic administration. Then repeat.

The pattern is familiar enough that it feels like a natural law that politics must go on this way.

Since the 1970s, progressives, organized labor, and (much less influentially) democratic socialists (collectively for the rest of this piece: “the left”) have consistently failed to intervene effectively in step two of the downward spiral. As a result, center-right Democratic administrations have consistently ignored or only paid lip service to the needs of the party’s working-class base. Brief deviations from this record (Obamacare’s expansion of Medicaid and extension of health care subsidies, Biden’s American Recovery Plan Act and the Inflation Reduction Act) have been political flops because their benefits have taken a long time to roll out or have been very temporary, and because most of these efforts have been channeled through “public-private partnerships,” and sometimes because people aren’t even aware of them.

The left, on the other hand, typically holds on to its role as a champion of the base’s interests, but it has also almost always been unwilling to aggressively fight the “blue team.” (The exception proves the rule: Bernie’s inspiring 2016 and 2020 presidential bids). Moreover, the left has never figured out how, once the party’s base has soured on the blue team, to take advantage of the disappointment. Resignation and flirtation with the right are consistently where disappointed Democratic voters go instead. So the outcome of new Democratic administrations has repeatedly been a drop in turnout and swings to the GOP, rather than a swing to the left.

Breaking Free From the Downward Spiral

One question motivated my Jacobin piece: Is there anything that Bernie and organized labor could do next year to extract us from that downward spiral? I argued that there is. Bernie now has a limited but real progressive agenda for a Kamala Harris administration, including a demand for a cease-fire in Gaza and peace and justice for Palestine as well as a list of redistributive measures and democratic reforms (read the piece for a summary). If enacted, the agenda could be a game changer. A game changer in the sense that delivering reasonably big gains for working people would change how regular people think about politics, and would potentially make them much less susceptible to right-wing answers to economic anxiety.

But enacting that agenda would require that Sanders and labor face reality: most Democrats — Harris very much included — are not enthusiastic supporters of even Bernie’s limited program for 2025. They will have to be forced to make these kinds of concessions, just as Lyndon B. Johnson’s administration, and Franklin D. Roosevelt’s before him, were pushed from below to reluctantly build a welfare state. That means Bernie and labor will actually need to lead a fight against the party if they want to break the pattern of the past.

And what if they fought in 2025 and still came up empty? In that case, they would be better placed to enter the 2026 midterm elections presenting a left-wing alternative to the Democratic Party. Primary and general elections challenging electeds on the party’s conservative wing would be much more viable. Popular frustration with Democrats who always have excuses for why they can’t deliver for workers (but who can move heaven and Earth to deliver for donors, the corporate world, and the state of Israel) would finally have an outlet to the left.

Is There Any Point in Trying?

That was, in summary, the argument of the piece. But as I understand Danny’s criticism, his concern lies elsewhere: given that Sanders and labor acting in this way is unlikely, is there any point in trying?

There are two reasons democratic socialists need to articulate a credible strategy for 2025, even if the odds of success are long.

First, a cynical take — that nothing can be done nationally — amounts to telling activists on the left: “Abandon all hope ye who enter 2025.” Not only does an “everything is fucked” message demoralize our base, it also risks becoming a self-fulfilling prophecy, leaving us ill-prepared to act nationally in the next opening.

Breakthroughs happen even in national politics, almost always at unexpected moments, and those who are best positioned to act when those moments come are those who are 1) well organized nationally and engaged in national politics, 2) have an analysis of the situation, and 3) whose demands and vision have been tested and are at least somewhat widely known. Lenin’s quote that there are “weeks when decades happen” is still one of the best pieces of strategic advice for leftists. Being prepared for a breakthrough requires at least a low level of mobilization and activity in the years leading up to those weeks. A strategy of pushing and persuading Bernie and labor to take a more aggressive stance toward the Democratic leadership is — as I see it — the best way that the democratic left can stay mobilized and engaged in national politics at a difficult time.

Second, abandoning the terrain of national politics by refusing to have a perspective on what needs to be done nationally also amounts to abandoning those on the democratic left whose focus is national. The democratic left today includes leaders and assistants in important unions and national social movements, activists staffing congressional offices, and intellectuals and propagandists thinking and articulating a left perspective on national politics. If democratic socialists decline to put forward a real strategy for national politics, these people will not leave their posts and focus exclusively on local politics and base-building. We will instead be abandoning them, leaving them to fend for themselves and allowing liberal forces to draw them in closer to a different vision for how to do national politics.

There is a reason why, despite the long odds, socialists throughout history have developed programs and strategies for national and even international politics long before they had much hope of shaping either terrain. And I’d say there’s a connection between their national perspective and their later success in building their forces: movements that set ambitious goals for themselves sometimes rise to meet the challenges they set themselves. (The same can’t be said for small left-wing sects, of course, but democratic socialists in the United States can be confident that we’ve left the sect days behind us.)

Setting Our Sights on the 2030s

When DSA was looking for a direction in the late 2010s, excitement around the idea of electing democratic socialists to Congress and playing a meaningful role in Bernie’s 2020 presidential campaign served as an important near-term horizon that we could work toward. A lot of the excitement around Shawn Fain’s proposal for some kind of major action by organized labor on May Day 2028 has helped prove that setting near-term, ambitious goals can have a mobilizing effect.

Similar ambitious thinking is needed for national politics. The prospect of democratic socialists working along with Sanders and reformed unions to offer an independent, left-wing option in the next few years, with an eye toward building a radically different and more favorable political terrain in the 2030s, could serve that purpose.1 There’s no guarantee Sanders and labor will be willing, but it’s a goal worth working towards.

(If you’re interested in thinking more about these ideas, and also want to hear my coauthor Nick French and I talk about these questions and more with the good people at the YouTube channel Left Reckoning, you can check out our recent show with them here.)

I’ve mostly talked recently about a strategy for the left in the context of a possible future Harris administration. Similar thinking is needed for the at-least-as-likely scenario of Trump’s return to power.

this sounds great but more or less assumes that dems hold the senate - what does a left attitude to a harris administration that is limited only to executive action look like? because the approach to biden on that has been unsuccessful.

also worth remembering that the right's slow takeover of SCOTUS has been a 50 year project.