The Real Bernie Model

Bernie will speak as a loyal party member at the Democratic convention. But that’s a break from the first 45 years of his political life, which are still a model for independent left politics.

This is part of a series of articles about socialist electoral strategy and party building. The first article is “Why Do Socialists Run as Democrats?” The second article is “The Junior Partner Strategy.” This is the third article.

Bernie Sanders is set to speak at the 2024 Democratic National Convention. That’s very much in keeping with his recent record. Sanders has been a loyal supporter of much of Joe Biden’s administration (with some notable exceptions, for example in his recent criticisms of Biden’s support for the atrocities in Gaza), and he has positioned himself as Kamala Harris’s most prominent left-wing supporter. Boosting Harris’s campaign will be the focus of his speech tonight. I’d be more than surprised if he tried to push her leftward on any question, let alone offer any strong criticism of the Democratic Party.

For democratic socialists looking for models for how to do independent politics, Bernie’s recent pivot towards being a trusted figure within the party poses a challenge. For many on the democratic left (myself very much included), Bernie’s 2016 campaign is still a key reference point. His ability to persuasively champion major reforms like Medicare for All and mobilize a mass base for democratic socialist politics is unmatched, and he is still — with good reason — a leading figure on the left. Yet his recent move from outsider to party insider can’t be reconciled with a commitment to independent political action and the goal of building a new party for working people. (Those ideas used to be key to Bernie’s politics, and ones he would defend in friendly debates with DSA.)

What to do? To borrow from an obscure Marxological debate about whether there was a significant difference in the work of the “Young Marx” and the “Mature Marx,” I want to defend the Young Bernie of 1972–2016 from the Mature Bernie and his acolytes today. The Young Bernie is still proof that independent left-wing politics can work. I’d also wager that the Young Bernie’s long independent record, which climaxed in his insurgent 2016 campaign, did much more to nudge the Democratic Party left than any of his recent efforts to work on the inside track. And from the Young Bernie’s years of experience we can draw at least five lessons for how to do independent politics effectively.

Lesson #1: Champion Popular, Significant, and Winnable Reforms

If you interviewed 100 people and asked them to tell you a single issue that Kamala Harris is the champion of, or cares strongly about, I doubt one person could answer. But if you asked people the same question about Bernie, I think the majority would point to Medicare for All. Bernie has been a consistent and relentless champion of single-payer health care throughout his entire career. It’s a popular and desperately-needed policy. It’s also a very significant and winnable reform. Unlike many liberals and progressives whose focus lies on very modest incremental fixes to social problems, Bernie has always fought for a health care policy that is big and hardly an incremental step forward. And unlike some on the far left who might prefer to focus on more maximalist fights that are not achievable under capitalism (what the Trotskyists sometimes call “transitional demands”), Bernie has always foregrounded a reformist agenda that could be won this side of “the revolution.”

Bernie’s independent political career was built on fighting for these kinds of popular, significant, and winnable reforms. He’s been a consistent “socialist reformist,” in the best sense of the term. Without those big but winnable reforms, his career would have looked like those of so many other politicians — bereft of real ideas that could change people’s lives, focused on personality and rhetoric about “values.”

Lesson #2: Lose, Lose Better, and Then Win

The Young Bernie was no stranger to losing. Between 1972 and 1989, Sanders lost every one of his six statewide elections in Vermont. Those losses were compensated for only in his second decade of political work when he finally won three consecutive elections for mayor of Burlington. Yet even while serving as mayor, Sanders took time off to run for governor and Congress in 1986 and 1988 — and lost again each time.

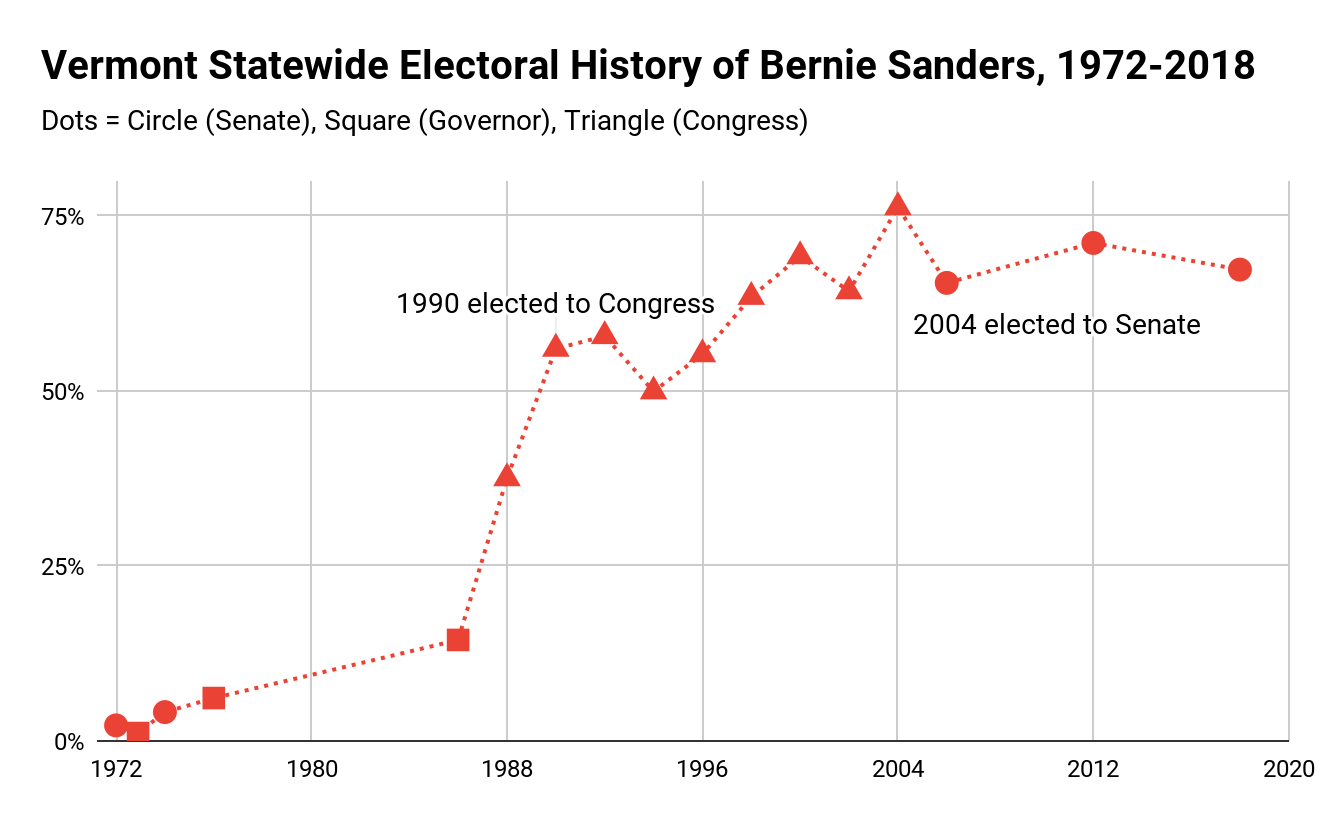

The key to Bernie’s success was that he was not afraid to lose in an election if it gave him a chance to organize his district (in each of these six losing elections his “district” was the entire state of Vermont) and popularize his politics. And in each election Sanders’s statewide support steadily rose, from less than 3 percent in his first two runs in 1972 to 4 percent in 1974, 6 percent in 1976, 14 percent in 1986, 38 percent in his last losing effort to get elected to Congress in 1988, to 56 percent in his breakthrough victory in 1990 and wins in the 60–70 percentage range in the last 20 years.

The lesson to be learned from Bernie here has two parts: First, an aspiring left-wing independent can’t be afraid of losing. And second, aspiring independents have to keep running election after election in the same district to steadily built up support. “Lose, lose better, and then win” would be a fitting motto to borrow from Bernie’s career.

Lesson #3: Don’t Fear Being a Spoiler

A common motivation for socialists to run as Democrats is that they don’t want to “spoil” an election and help elect a Republican.

As I’ve argued before in this series, this motivation is most often employed to justify running as a Democrat in parts of the country where there is no plausible chance that a Republican could win. Nevertheless, in Vermont in the 1970s and ’80s Bernie did risk spoiling not one but three elections. In the 1974 Senate race and the 1986 gubernatorial race, Sanders took enough of the vote that the Democrat won less than 50 percent and put the Republican within striking distance of victory. And in 1988, Bernie did spoil the Congressional election by entering the race as an independent and splitting the anti-GOP vote. (Though it’s worth noting that he actually came out ahead of the Democrat, who came third in the race. Who is really “the spoiler” in these kinds of elections?) Bernie’s 1988 run helped elect Peter Plympton Smith (a son of a Burlington banker with a great Brahmin middle name) to Congress as a Republican. Undeterred however, Bernie ran again in 1990 and finally bested Peter Plympton.

(There are limits here though that I suspect even the Young Bernie would have respected. Sanders rightly decided in 2016 not to run as an independent and risk contributing to the election of Donald Trump. Sanders’s earlier runs were based implicitly on an understanding that running and risking spoiling the election would not elect a far right politician to a powerful executive office.)

Lesson #4: Independent Left-Wing Candidates Can Win Big in Red States

The electoral map we’re familiar with, with most of New England painted in the deepest shades of blue, was not always the way of things. Until 1992, Vermont was one of the most solidly Republican states in the country, so much so that in 1936 Vermont was one of only two states to vote against Franklin Roosevelt. Starting with the first election in which a Republican Party candidate ran in 1856 and running up until 1992, the GOP won every single presidential race in Vermont with the exception of the election of 1964. In the two elections preceding Bernie’s first statewide win in 1990, Ronald Reagan won the state with a 17 percentage point margin in 1984 and George H. W. Bush won it with about a 4 percentage point margin in 1988. Although Bill Clinton finally won the state in 1992 with 46 percent of the vote, the combined vote of the GOP and the right-leaning populist campaign of Ross Perot was more than 53 percent. With one two-year exception, between 1856 and 1990 Vermont was always represented in the House of Representatives by Republicans.

Yet Bernie finally won the state in 1990 with 56 percent of the vote, and as a democratic socialist no less. And in 1992, when the right took a combined 53 percent of the state’s presidential vote, Bernie walked away with the congressional election with 58 percent.

The point is that even — or especially — in states where Republicans seem to clearly dominate state politics, left-wing candidates can make surprising breakthroughs as independents. This is even more important today, at a time when partisan loyalties are especially strong but solidly red states often vote for surprisingly progressive initiatives — like abortion rights in Kentucky, Kansas, and Montana in 2022; minimum wage increases in Nebraska (2022), Florida (2020), and Arkansas and Missouri (2018); and Medicaid expansions in Missouri and Oklahoma (2020) plus Idaho, Nebraska, and Utah (2018).

Until Democrats and those of us on the left can break the stranglehold of the right wing on red states, elections will continue to be decided by razor-thin margins and Congress will continue to be stuck in gridlock, making progressive policy initiatives dead on arrival. Following the Bernie model and running independent labor and left candidates in red states could be a novel and important means to break this stalemate.

On this point, campaigns like the one being fought by Dan Osborne — a Bakery Workers (BCTGM) member and strike leader in the 2021 Kellogg’s strike who is running for Senate this year in Nebraska as an independent — are a model to follow in the future. A key motivation for Osborne’s independent run is to get away from the Democrats’ destroyed party brand, as a former Nebraska Bernie delegate and supporter told Steve Early in a Labor Notes piece last year. Osborne faces an uphill fight, but even if he loses this year he could set himself or another labor activist up to “lose better” and then eventually win in the future.

Lesson #5: There Is a Way to Be Independent and Join the Fight Against the Right

For decades, a Republican Party hurtling rightward has posed a challenge to those of us on the left who want to remain independent of the Democratic Party but also want to help defeat the far right. This has always been less of a problem for explicitly socialist organizations that can’t hope to influence the outcome of a presidential election even if they wanted to. But it is a serious problem for socialist electeds and left-wing union leaders who lead larger social bases and whose endorsement and campaigning decisions do matter.

While in 2020 and 2024 Bernie has been a vigorous supporter and campaigner for Democratic presidential nominees, his approach used to be different. Without denying the reality that in some elections there really is a “lesser-evil” and that voting for that candidate might be necessary, in the past Sanders was careful to make the case for lesser-evil voting in the form of critical support. This helped him stake out an independent position to the left of Democratic presidential candidates whose politics he clearly did not want to endorse.

In 1996 for example, Sanders focused on defeating Bob Dole. But he made clear that he opposed Clinton’s agenda on health care, welfare reform, free trade, and military spending, as well as Clinton’s opposition to gay marriage. Sanders put his position plainly in his memoir reflecting on his thinking at the time: “Do I have confidence that Clinton will stand up for the working people of this country — for children, for the elderly, for the folks who are hurting? No, I do not.” Yet Sanders was prepared to vote for Clinton and to lead his base to do the same in order to beat the right: “Perhaps ‘support’ is too strong a word. I’m planning no press conferences to push [Clinton’s] candidacy, and will do no campaigning for him. I will vote for him, and make that public.”

* * *

There are negative lessons in Bernie’s independent career too. Bernie’s disinterest in and even opposition to trying to build a real independent, mass-membership democratic organization is the most glaring of all. But as socialists continue to think through what a viable and independent electoral project for the 2020s and 2030s might look like, the career of the Young Bernie is still an invaluable starting place. And as the 2024 general election approaches and the perennial pull on leftists to close ranks uncritically and inside the Democratic Party grows stronger (this time with the Mature Bernie leading that charge), it’s especially important to remember that there are alternatives.

I don't get a strong sense from your essay as to *why* Young Bernie morphed into Mature Bernie after the 2016 campaign. Would Sanders or his supporters even agree that there *was* a change after that campaign? Was the fact that the 2016 campaign made him a well known national figure responsible for that change -- and what other factors played a role? After that campaign, did he conclude that he had reached the limits of what an independent, non-major-party-aligned professional politician could accomplish in the U.S.?