How Democrats Changed Their Social Base to Defend Their Neoliberal Program

Democrats’ right turn 30 years ago broke the party’s historic working-class base. As workers left the party, party leaders then treated those losses as an opportunity to pivot to the middle class.

It’s hard to look away from the political storm wreaking havoc on this country. As someone who mostly thinks and writes about the left’s electoral strategy and our relationship to the Democratic Party, I’ve had a hard time writing about my usual subjects.

But last week, Catalyst published a long-form article of mine, “The Democrats Embrace Dealignment.” That’s as good a time as any to take a short break from the chaos and think about something somewhat removed. So here’s the capsule summary of the argument (though I hope you’ll check out the full piece over at Catalyst):

In the article, I take up and argue for Bernie’s pithy explanation for the Democrats’ 2024 drubbing. “It should come as no great surprise that a Democratic Party which has abandoned working class people would find that the working class has abandoned them.” I think he’s right on the money.

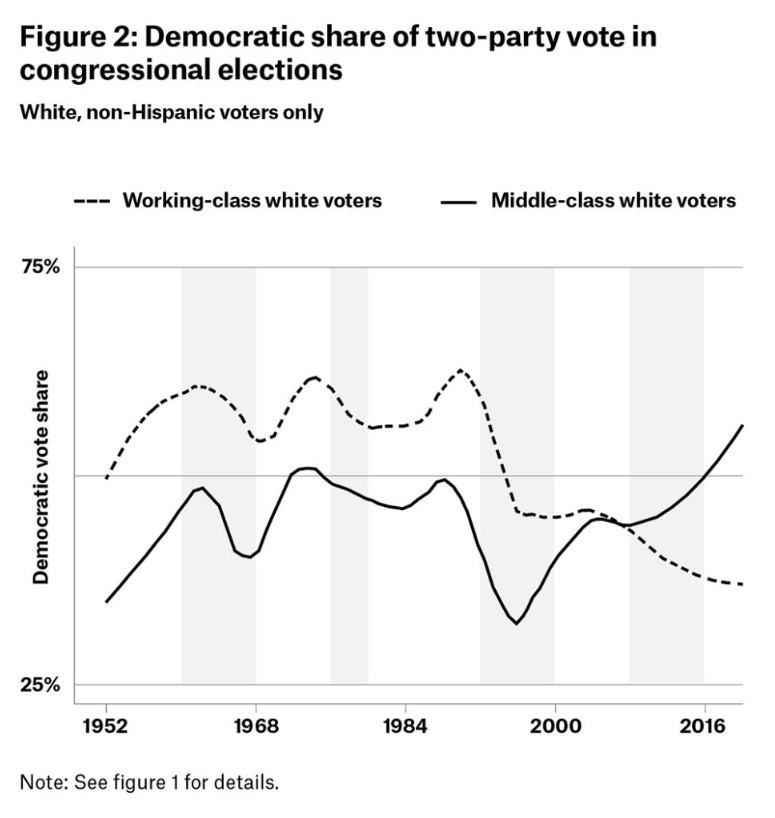

A lot has now been written about the extent of class dealignment, which is the shorthand label for the process of workers and center-left politicians drifting apart. My article focuses on explaining how class dealignment came about, and to do so I start by identifying its origin point in the 1990s. Up until the ’90s, Democrats could count on majority support from working-class voters in congressional elections, while Republicans depended on the middle class (see the figure below for what that looks like — more detail in the full piece). And although Democrats lost every presidential election between 1968 up until 1992 save one, which meant they lost a majority of voters from both classes, their presidential coalitions disproportionately relied on working-class support as well.

That historic coupling between working-class voters and the Democratic Party came undone because Democrats pursued a very different economic strategy under Bill Clinton than they had pursued before. Party leaders made austerity, free trade, and financial deregulation their version of “peace, land, and bread.” I go into some detail in the piece about why Democrats made this turn, but suffice it to say that the results weren’t pretty — especially since the party’s right turn came in the middle of deindustrialization and its free trade policy in particular became an easy target for critics. As I also show in the article, leading Democrats at the time, including many in the party’s economic policymaking circles, were fully aware of the negative consequences their program would have for the party’s working-class supporters. They pursued the program anyway.

Crisis and Opportunity for the Democrats

It didn’t take long for voters to punish Democrats. The 1994 midterm election was a wipeout — the first time since 1952 that Democrats lost control of the House of Representatives. Democrats were then locked out of control of Congress for the next twelve years, the party’s longest losing streak since the 1920s.

All this amounted to a major crisis for the party. But rather than change their economic program, Democratic leaders gradually coalesced around a different solution to their ills: change their social base. Here’s Al From, CEO of the party’s centrist faction, the Democratic Leadership Council, who put the party’s new strategy perfectly:

The New Economy is creating a new electorate that demands a new politics. The sharp class differences of the Industrial Age are becoming less distinct as more and more Americans move into the middle and upper-middle classes. The New Deal political philosophy that defined our politics for most of the 20th century has run its course; the political coalition it spawned has been split. Like Humpty Dumpty, the New Deal coalition cannot be put back together again. The new electorate is affluent, educated, diverse, suburban, “wired,” and moderate. And it responds more favorably to the New Democrat political philosophy than to any other.

In pursuit of organizing this new wired constituency, Democrats increasingly focused their attention in the 2000s on affluent, suburban parts of the country. These areas were the terrain deemed to be most fruitful for the party to pick up seats in Congress and votes in presidential elections.

On the policy front, Democrats’ top power brokers, financiers, and economic strategists became increasingly concerned in the 2000s that the mood of the country was turning against the neoliberal order they had helped design. It’s in this period that the party’s top strategists, many with Wall Street connections, began to talk about rebuilding the social safety net. That paved the way, after Democrats’ landslide victory in 2008, for the Obama administration’s push to expand Medicaid access and subsidize health insurance premiums through the Affordable Care Act.

But these efforts had pretty severe limits. The party’s unshakable commitment to working with capital on any proposed reform program gives capital a veto power over the party’s policy agenda. That was true for Bill Clinton, it was true for Barack Obama, and it was true for Joe Biden (something I first wrote about back in 2021). In the Catalyst piece, I call this the “corporate filter,” because party leaders never seriously pursue policies that can’t get significant business backing. That’s why every Democratic administration since Harry Truman’s has promised to reform labor law and none have delivered.

The payoff of the piece is to put the blame (or the credit, if you’re one of the many Democrats who view the party’s “brahminization” as a good thing) for class dealignment on the party’s leadership, and in particular on its business-friendly economic program. As I argue at the end, the fundamental assumptions of that economic program — especially giving veto rights to the leading sections of capital over the party’s reform agenda — have not changed at all, even under the Biden presidency.

The Upshot for the Left

What this means for the left and the labor movement’s electoral strategy depends on how optimistic you are about our chances to remove the party’s leadership. It’s the party leadership that has to be dislodged and replaced if there’s going to be any hope of pursuing both a much more ambitious (and less business-friendly) reform agenda and a new electoral strategy focused on building a working-class majority.

If you are optimistic that a new party leadership can be installed in the near term — by replacing Chuck Schumer and Hakeem Jeffries as the party’s congressional co-consuls and then by winning the 2028 presidential nomination battle for someone from the progressive left — your marching orders are clear.

But for my part, I can’t see how that could come to pass. To begin with, replacing Schumer and Jeffries would require replacing 50 percent + 1 of the existing crew of Democratic senators and representatives. Without a left majority in both Democratic caucuses (something that is, I think, inconceivable), Schumer and Jeffries will be secure in their leadership roles. There has been talk of replacing Schumer, but given the present composition of the Democratic Senate caucus, that would be a cosmetic change if it happened. They’re not putting Bernie Sanders in charge of the party. Prospects for winning the party’s 2028 presidential nomination seem equally bleak, especially as the party’s middle-class, suburban makeover makes it harder and harder for a genuine candidate of the labor left to grab the nomination.

Luckily for those of us looking for an alternative, we’ve got examples to look to. The real Bernie model — the story of how an unapologetic, pro-labor, independent, democratic socialist conquered Vermont back when it was a red state — should be better known. As should projects like the Vermont Progressive Party, California’s Richmond Progressive Alliance, and union activist Dan Osborn’s run for Senator in Nebraska last year. Independent politics can work if it’s pursued seriously. For the last decade, much of the left’s electoral energy has been poured into trying to work within the Democratic Party and hoping that its leadership can be nudged left. As I conclude my Catalyst piece, I think it’s past time that we change direction:

If the 2024 election puts the labor left on a more aggressive course to challenge the party, it could yet have some positive long-term effects. We can work toward that change. Any ambitions for developing a robust response to the ongoing climate catastrophe, rebuilding an economy that guarantees good work and social support for all, securing racial justice and the defense of civil rights and personal freedoms, and forging a more peaceful and cooperative world order — to say nothing of loftier aspirations for winning a democratic socialist future — rest on finding a more independent and confrontational approach to a Democratic Party that has fully shorn itself of its New Deal heritage.

I’m a democrat who will never defend neoliberalism! Abundance is a crock.

Good article, reminds me of this one: https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2016/10/how-democrats-killed-their-populist-soul/504710/