Political Parties Are Not Illegal in the US

A popular argument on the left holds that political parties are essentially illegal in the US because they are so regulated that they can’t manage their own affairs. This is not true.

In ongoing intraleft debates, many arguments are thrown against the idea that the left needs its own political party.

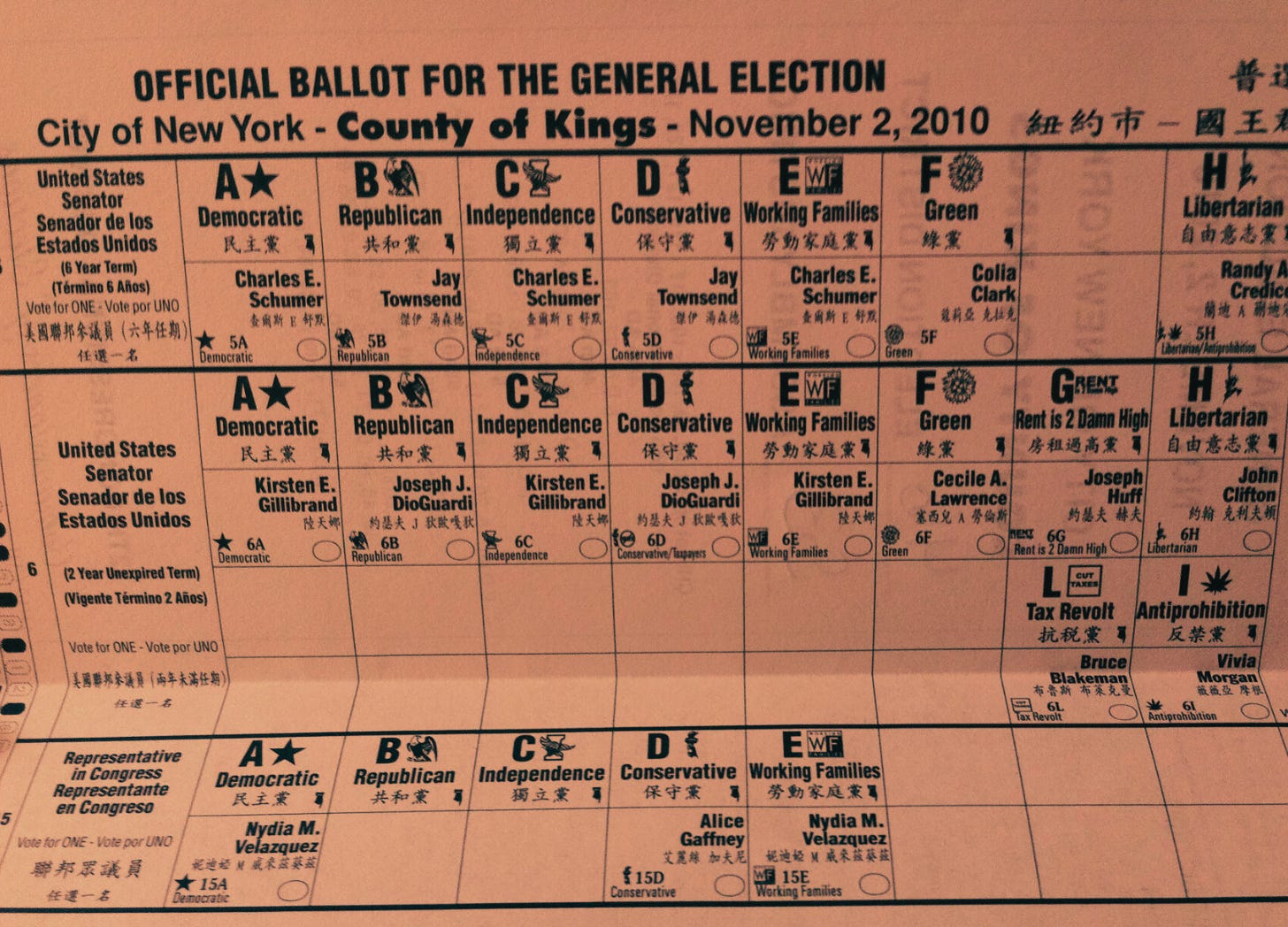

One such argument goes like this: Maybe it would be desirable for socialists, union organizers, and movement activists to come together to build an independent political party in the United States with its own name and ballot line, but it is impossible to have one given how parties are regulated by the government. This is because — so the argument goes — anyone can register with a party regardless of whether they really agree with it, parties are required to use government-administered nomination processes to choose their candidates, and anyone registered with a party can vote and/or run in its primaries.

These alleged facts about how parties are regulated supposedly make it impossible for political parties to exist in any meaningful sense in the US. Anyone can join a party and run as a nominee of that party, even if they don’t agree with it and hold ideas that are totally opposed to the party’s program. If hostile forces try to hijack a party’s ballot line, the rules that govern parties make them helpless in the face of such raids. In a certain sense, parties in the US don’t even really exist — you could go so far as to say that the way that parties are regulated by state governments means that real political parties are illegal in this country.

Again, this is not my argument, but it’s a common one that will probably sound familiar to those versed in the Democratic Socialists of America’s internal debates. And it is the alleged permeability of parties in the US, especially the strong rights of anyone registered with a party to run for its nomination and vote in its primaries, that makes DSA’s strategy of working within the Democratic Party possible.

This is the argument that Michael Kinnucan made recently, now published on the blog of DSA’s Socialist Majority Caucus under the title “Political Parties Are Illegal in the United States.” Michael’s article is built around a hypothetical case in which leftists form a new “Socialism Party.” Such a party, Michael argues, would be helpless to stop “milquetoast liberals” from winning its nomination and would be incapable of un-endorsing candidates who abandon or reject from the start the party’s program. The left might launch an independent labor party, but its distinctive politics could quickly be overwhelmed by libertarians, MAGA Republicans, or Abundance liberals. “[A]ny state rep candidate who can get a couple dozen people to check a box on a form in any district in the state can run as an official candidate of the Socialism Party and we can’t do a thing about it” (emphasis added).

For anyone interested in building a group of elected officials and grassroots activists that are united around a shared strategy and program, organizing as an independent party that is vulnerable to this kind of raiding and potential entry by hostile candidates could in fact be extremely counterproductive. “Procedural regulation,” Michael writes, “makes candidate accountability impossible.” Therefore, by becoming a formally recognized, independent party, the hypothetical Socialism Party surrenders any right to control who is and who isn’t a voter in its primaries or a candidate on its ballot line — even if a potential candidate disagrees with the Socialism Party on, for example, as serious an issue as the genocide in Gaza. “Do members of the Socialism Party want to strip SP elected officials of party membership if they support a war or genocide? Too bad, the state says those elected officials will still be eligible to run and vote in SP primaries.”

It’s not just the hypothetical Socialism Party that faces these problems, according to Michael. The major parties do too. “If the Democrats had been able to disqualify AOC from running as a Democrat, or disqualify left-wing voters from voting in primaries . . . no doubt they would have. But they can’t.”

To sum up, Michael writes:

The state has set rules such that it is ILLEGAL for us to have an organized group of socialists who make collective decisions and have those decisions be binding on an electoral US party. It's not merely hard or impractical — it's impossible.

Parties Don’t Work That Way

As an objection to building an independent party, Michael’s argument is an interesting challenge. But it’s based on a number of assumptions about how parties work that don’t seem to be accurate.

I have not reviewed every state’s electoral codes governing parties. But I’ve examined a few, and I haven’t found any so far that support Michael’s account of how parties are regulated. Instead, it seems to be the case that state laws explicitly protect a political party’s right to define what it means to be a member and also provides clear mechanisms by which a party can enforce that definition. After a hearing and a decision is reached by the party leadership that a voter is not in sympathy with the party’s principles, party leaders can instruct the board of elections to unenroll said voter from the party. Unenrolling a voter makes them ineligible to run for the party’s nomination or even vote in its primary.

Take New York, for example, where Michael and I both live. If you look up § 16-110(2) of the New York state election law, there is a clear procedure that parties can use to unenroll individuals or candidates — a means by which a party could prevent candidates from running on that party’s ballot line or even prevent a group of voters from voting in that party’s primary. You can register as a Democrat in New York, but if the party leadership decides you do not meet its definition of what a Democrat is, they can unenroll you.

There are a number of legal cases that involve the application of this procedure, including a case in 2009 (Walsh v. Abramowitz) in which hundreds of New York’s Police Benevolent Association members attempted to enroll in the Conservative Party and were then disenrolled from the party after Conservatives held a hearing and expelled them for entryism (it's a wild case for many reasons).

Contrary to what Michael seems to say, the courts in the cases I’ve read repeatedly stress that it is essential to protect parties’ ability to expel those in fundamental disagreement with their program. Only by having this power can parties actually define what it means to be a member of their party and offer distinct politics and programs to voters. Some of the cases I've read emphasize the need for such a mechanism to protect minor parties in particular. These small parties are otherwise especially vulnerable to raiding because their nomination contests involve many fewer voters.

Against what Michael and some others in DSA argue, then, parties in the United States very much are legal and have the legal right to defend themselves from raiding by hostile forces and from candidates whose politics are not in line with the party’s principles.1 The fact that such mechanisms are rarely used in the US speaks to the ideologically-broad nature of the Democratic (and, until recently at least) Republican parties — but that’s a choice those parties make, not a rule forced on them.

There are other, more compelling reasons to do electoral politics inside the Democratic Party. I wrote about one that I disagree with but take seriously last year: that by being a “junior partner” in the Democratic Party fold, socialists might be able to win important reforms. But “parties are illegal” is not a compelling argument for working inside the Democratic Party. We should add that to the list of not-great reasons for doing so, alongside flawed arguments that the spoiler effect or restrictive ballot access laws pose insurmountable challenges to running serious independent general election campaigns.

Follow-Up

Since I wrote this reply, Michael replied to some of the points above. Michael says that the point in his piece was that having an independent party does not in and of itself improve a political project’s ability to discipline its elected officials.

This is a different point from the original argument that political parties in the United State are illegal. I’m glad Michael wrote the original argument down in article form, because it’s one that I’ve heard many times in DSA and one that needs to be debated more.

But the new argument Michael puts forward is also interesting. And on this point, I think I agree with him. Having a distinct labor or socialist ballot line and an independent party identity would not automatically make it easier for leaders to build a unified party.

I think it would help. The fact that elected officials of an independent labor party would no longer caucus with Democrats inside legislatures would, I imagine, make them less susceptible to pressure from Democratic leaders to spurn the left. And being part of a distinct, publicly-recognizable party does generate a degree of unity. Think of how united Democrats and Republicans are today; there’s a reason people refer to these as “tribal identities.” But a formally independent party — desirable as it is for many other reasons — is not the key to creating a unified bloc of elected officials and members.

Consider for example the Labour Party in the UK. Like other parties in the UK, it is usually a fairly unified group in Parliament. But there have been times when that unity has fallen apart. In 2003, for example, more than 100 Labour members of Parliament voted against Tony Blair’s push to join the Iraq War. They were not forced to vote with the majority of the leadership just in virtue of being Labour Party members.

The point here is that having an independent party is not identical with having a unified party, in the United States or abroad. Political unity and discipline are not won simply by having an independent party. They are the result of building up a party culture that respects an internal decision-making process and the outcomes of that process, and a result of building up a sense that “we’re all in this together” and that we have to act together. Michael is right these qualities are not created simply by being a formally-recognized political party.

But again, that’s a very different argument than the original idea that parties are illegal in the United States. It’s time we put that argument to bed.2

The closest I’ve seen so far to a regulation that supports Michael’s claims is a court case in New York in 2002 that ruled the Democratic Party’s efforts to unenroll a state senator from the party (Rivera v. Espada). The court found that the party illegitimately used a speech in the New York State Senate by that state senator to support its expulsion case. New York’s State Constitution protects state legislators from being questioned for what they say and do politically in the state legislature. It is indeed a weird — and undemocratic — rule of New York politics that legislators’ actions in the state legislature are considered “privileged” in this way (I don’t know if other states have such rules). But even in this case, the state court found that had the party used other evidence to justify its expulsion decision, it would have been on much firmer ground in doing so and the court would likely have deferred to the party. The court wrote: “Election Law § 16-110(2) assigns the task of determining whether a voter ‘is in sympathy with the principles’ of his or her political party to a leader of that party — the County Committee Chair — and limits courts to deciding whether this determination is ‘just.’ This division of responsibility reflects a legislative choice not to involve courts in determining party ‘principles.’ Thus, the court's role is to ensure that the County Committee Chair reaches a decision on the basis of sufficient evidence and does not consider inappropriate factors.”

And for that matter, it’d be good to acknowledge that the Democratic Party’s legal right to expel people for being in disagreement with the party’s program and goals could be a threat to DSA in the future. The law seems to be clear that party leaders could unenroll DSA members, candidates, and elected officials from the party in the future if they decided that that was in their interest to do. This runs against a claim Michael makes at the end of his original piece. He writes: “‘The’ Democratic Party is legally bound to let us run on ‘their’ ballot line in ‘their’ internal (primary) elections. If they weren't — if the laws were different — then we'd find it both necessary and also possible to form a ballot-line third party. As things stand, it is not necessary and also not possible.” As I’ve tried to show above, the law says exactly the opposite. Does that mean the Democratic Party is going to start expelling DSA members tomorrow? Definitely not. (And it’s worth asking why that’s the case.) Does it mean they could if at some point in the future they wanted to? It seems the answer to that is yes.

In Minnesota we don’t register for parties, and I assume that’s true in some other states. So you can’t be unregistered. The main party control is “endorsement,” and it’s very loose. Unendorsed Democrats win all the time, even for governor, like Tim Walz. Once third parties reach “major” status, they are vulnerable to takeover. The Legalize Marijuana Party became a major party in Minnesota and Republicans encouraged conservatives to use its ballot line across the state to create spoiler tickets. Minor parties have more control.

Of course what he means by “parties are illegal” is the “left’s conception of tightly controlled, member run parties, fully in control of membership and its ballot line like parties in Europe” is substantially illegal.

As mentioned in the comments, many more people live in open-primary states and/or nonpartisan registration states (like Georgia and most of the former Confederacy, but also the Great Lakes), which make the idea of a “party member” much more nebulous and the ability to remove party labels from candidates or nominees much more difficult without a court order compared to NY.

But in addition, the state-funded, state-ran nomination process allows the state to control the calendar and method of nomination, as we see in the conflicting trigger laws between Iowa and New Hampshire who threaten each other with earlier primary or caucus dates if one leapfrogs the other. This meant that when the DNC wanted to place the South Carolina Democratic primary first ahead of New Hampshire and Iowa, both Republican-ran states and their Democratic parties objected and threatened to hold their primary anyway. Furthermore, Georgia refused to move their Democratic primary ahead of their Republican primary, and the state government controls the means of party nominations.

OTOH, state parties give so much control to the state government as a cost-cutting measure to ensure broad participation in the nominating process, and both party supporters and independents see the primary as a direct means of popular control over the candidates. But they surrender their independence and quality control to these state governments in that process.

Most countries don’t do this. Why should we?